Now I Know My ABC's

Next Time Won't You Art With Me!

Not every language has a writing system, but every writing system can trace back to language. The evolution of writing systems have a lot to do with the individual language, culture, and repetition of communication within the culture. When writing develops, it is used to transmit information and share knowledge consistently and in greater detail than by spoken word alone.

The invention of writing is a gradual process, not a one-time event, however cool the mythology stories of the Norse god Odin and the Egyptian god Thoth are! Instead, writing systems usually start as pictures to represent spoken language.

Let’s figure out how to talk about how writing works. In writing. How meta!

Spoken language is made of sounds, called phonemes.

Writing is composed of codified marks or symbols referred to as graphemes, or glyphs.

Iconography, or icons, are very common across cultures, such as the heart, tree, or lightning bolt, but they have not been developed enough to be considered an entire language. So iconography is connected to writing and to art, but is not a written language of itself.

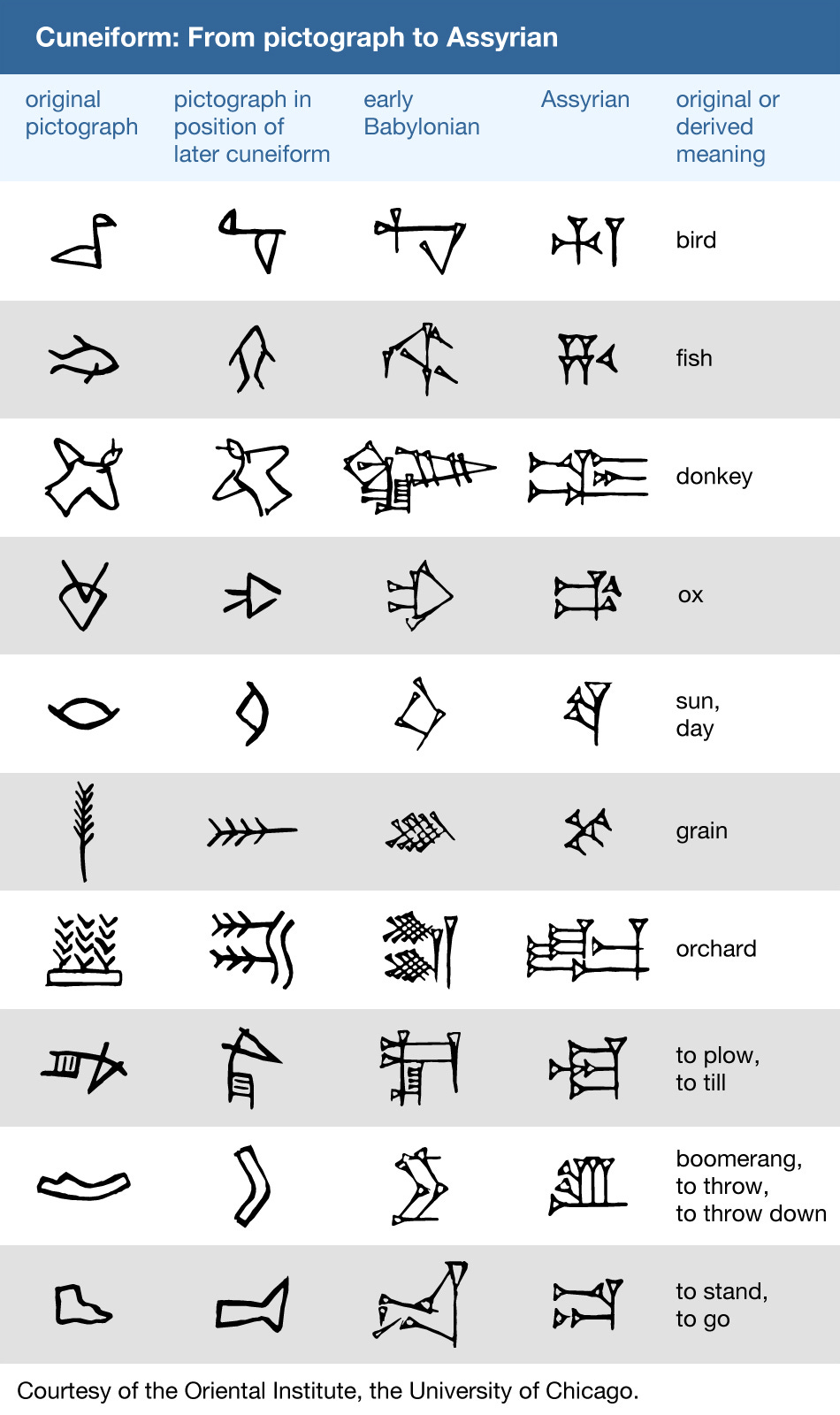

Through repetition, writing develops from pictographic representations to increasingly abstract representations of spoken language. They can be understood as different systems.

Picture writing systems use glyphs or simplified pictures representing objects, such as counting, constellations, or animals.

These glyphs may be mnemonic, or serving as a reminder,

pictographic, or direct representations, or

ideographic, using abstract symbols to directly represent an idea or concept.Transitional systems essentially combine glyphs with phonetic systems. The glyphs or graphemes become more abstract. They refer to the name of an object or idea it represents.

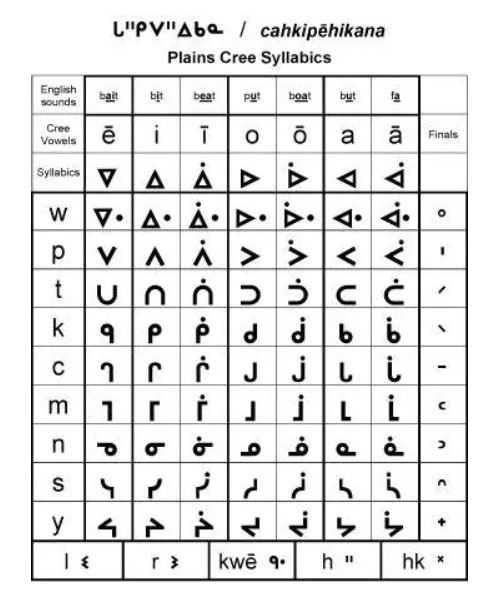

Phonetic systems use graphemes to refer to sounds or spoken symbols. In phonetic writing systems, the form is not directly related to meaning. They can be subdivided into smaller systems based on whether each grapheme refers to a word, a syllable, or a vowel/consonant.

These systems may be verbal or a logogram writing system, in which each grapheme represents an entire word. Examples of logogram systems include historic Egyptian hieroglyphs and contemporary Chinese writing.

They be a syllabic writing system, in which each grapheme represents a syllable or sound, such as Sumerian cuneiform, Cherokee, Cree, Inuktut, or the Japanese hiragana or katakana writing systems.

Or, they may be an alphabetic writing system. In an alphabetic writing system, each grapheme breaks syllables down into very basic sounds, and then the sounds are combined to make syllables, then words. Examples of alphabetic systems include Latin, Cyrillic, Kanji, Hangul, and Arabic writing systems.

The first examples of writing were found in ancient Sumer (Mesopotamia) between 3400 and 3300 BC, and much later in Mesoamerica around 300 BC, with the Aztecs and Mayans. Sumerian writing began as pictographs, then evolved into syllabic cuneiform. Aztec writing began as pictographs. Mayan writing used pictographs and developed a numerical system as well.

The next writing system arose in Egypt, though we don’t know whether it developed independently or after Sumerian writing through trade systems. Ancient China’s writing seems to have developed independently, and went on to inspire Japan’s kanji alphabet.

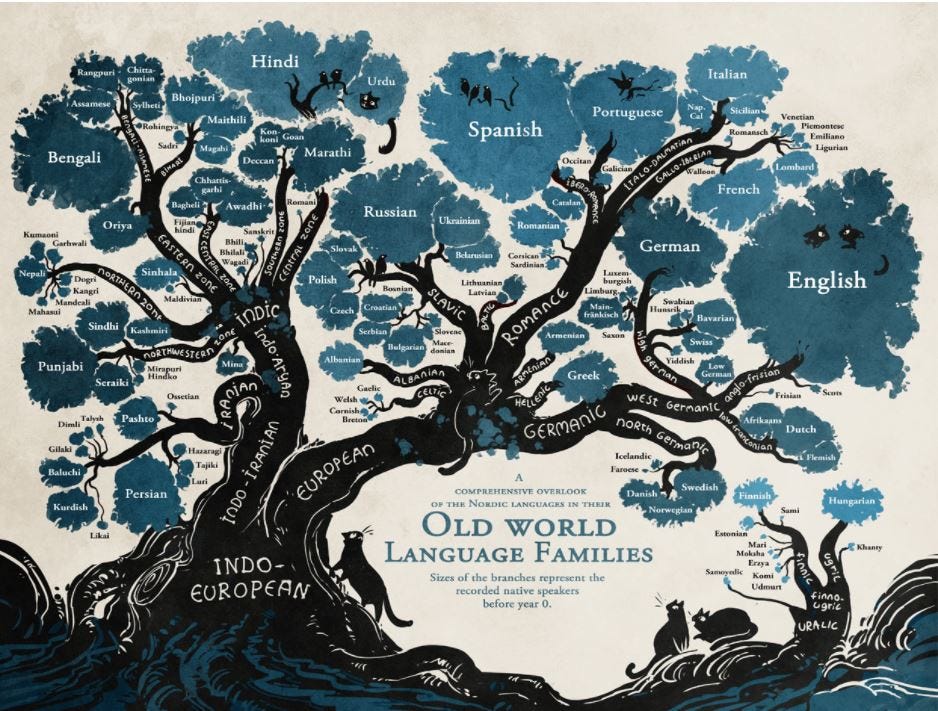

If we recall our earlier language tree, the English spoken language is a Germanic-based language, but its writing system uses the Latin or Roman alphabet, of Romantic language descent.

More specifically, our alphabet is developed from the Etruscan alphabet sometime before 600 BC. Writing in ancient Roman times was interesting because they sometimes mixed cursive and semi-cursive letters, and at one point they wrote forwards and backwards in mirror writing! Eventually the alphabet became more standardized with the rise of copying books in 15th century Italy. This led to the roman and italic typefaces we use today.

My art practice is all about exploring this connection between art and language. The reason why I am so fascinated by written language and especially with alphabets, is because I think it connects to art in a really simple and poignant way. I am able to articulate this connection because I came across a couple of studies of art analysis that were really transformative to my practice.

The first study relates to art development. In Rhonda Kellogg’s 1970 book, Analyzing Children’s Art, Kellogg describes how she studied children’s art looking for patterns of art development. She found 20 basic scribbles that can be repeated, combined, or isolated in different ways to create, as she put it, the building blocks of art.

The second study relates to cave art and art history. Geneviveve von Petzinger studies some of the oldest art in the world. In 2010, for her masters project Von Petzinger compiled a comprehensive database of all recorded cave signs from 146 sites in France, covering 25,000 years of prehistory. What emerged was 32 symbols, or graphemes, with 26 of those signs all drawn in the same style, which appeared again and again at numerous sites all over Europe.

Von Petzinger argues that these markings hint at the seeds of written communication. Since they are from 35,000-10,000 years ago and aren’t quite consistent enough to represent an alphabet, we can surmise that this cave art is actually the protosystem of writing leading to the development of Sumerian, Egyptian, and Chinese writing systems!

We can see that there are basic symbols such as lines, dots, and curves which we found in Kellogg’s children’s art, as well as more complex designs that appear in several places around the world in cave art. Seeing these sources together, we can view Kellogg’s and Von Petzinger’s work as catalogues of the specific mark-making that lead to both drawings and to writing. We can conclude that these drawings or marks develop into writing by eventually repeating enough to become codified. At this point, we can define the connection that exists between writing and drawing.

Drawing and writing are both all about mark-making.

These codified squiggles are taught to us, and we can read them and make pictures in our heads to describe such abstract and absurd concepts:

What is communication?

How does science work?

Why is the sky blue?

How do we think?

What is art?

How can we avoid making boring art?

Additional Resources:

The Alphabet Abecedarium: Some Notes on Letters. Richard A Firmage. Published by David R. Godine, 1994. ISBN 10: 0879239980 / ISBN 13: 9780879239985

“Comic Artist Maps the History of Languages with an Illustrated Linguistic Tree.” Emma Taggert, featuring Minna Sundberg. September 2017. https://mymodernmet.com/comic-artist-illustrated-linguistic-tree/

Analyzing Children’s Art. Rhonda Kellogg. Published by Mayfield Pub Co, 1970. ISBN 10: 0874841968 ISBN 13: 9780874841961

“Why are these 32 symbols found in ancient caves all over Europe?” Genevieve von Petzinger, TEDTalk. August 2015. https://www.ted.com/talks/genevieve_von_petzinger_why_are_these_32_symbols_found_in_ancient_caves_all_over_europe?language=en